The origin of the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel leads to a lot of speculation but there are many paintings of the breed showing a small spaniel in appearance in the laps of the aristocrats of Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. What we do know for sure is that the English refined the breed.

The Cavalier King Charles Spaniel of today is descended from the small Toy Spaniels seen in so many of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth century paintings by Titian, Van Dyck, Lely, Stubbs, Gainsborough, Reynolds, and Romney. These paintings show small spaniels with flat heads, high set ears, almond eyes, and rather pointed noses. During Tudor times, Toy Spaniels were quite common as ladies’ pets, but it was under the Stuarts that they were given the royal title of King Charles Spaniels.

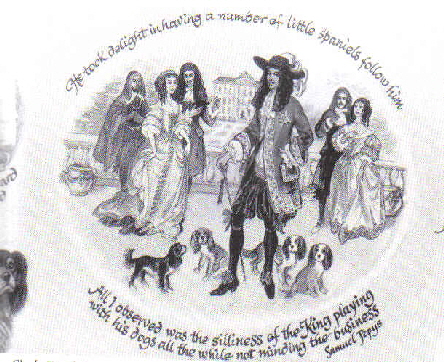

The name King Charles came from King Charles I and King Charles II although the first recorded appearance was with Mary Queen of Scots. It is said that a little spaniel walked with her to her execution under her skirting. He apparently stayed with her until someone took him away and two days later he himself passed away. The story goes that wherever King Charles II went so did his family of dogs (Cavaliers). History tells us that King Charles II was seldom seen without two or three spaniels at his heels. So fond was King Charles II of his little dogs, he wrote a decree that the King Charles Spaniel should be accepted in any public place, even in the Houses of Parliament where animals were not usually allowed.

This decree is still in existence today in England. They were owned by royalty and nobles, in fact most of the aristocrats of England and Europe. The name itself ‘Cavalier’ is supposedly given because of King Charles. He was known as the Cavalier King Charles and his parliament was known as ‘The Cavalier Parliament’ hence the name. After King Charles II, James II also adored the breed insisting they go everywhere with him even sea voyages. Other lovers of the breed were Henri III of France and Queen Victoria also loved the breed owning a Tri Cavalier named Dash. As time went by, and with the coming of the Dutch Court, Toy Spaniels went out of fashion and were replaced in popularity by the Pug.

One exception was the strain of red and white Toy Spaniels that was bred at Blenheim Palace by various Dukes of Marlborough. In the early days, there were no dog shows and no recognized breed standard, so both type and size varied. With little transport available, one can readily believe that breeding was carried out in a most haphazard way. By the mid-nineteenth century, England took up dog breeding and dog showing seriously. Many breeds were developed and others altered. This brought a new fashion to the Toy Spaniel – dogs with the completely flat face, undershot jaw, domed skull with long, low set ears and large, round frontal eyes of the modern King Charles Spaniel (also called “Charlies” and known in the United States today as the English Toy Spaniel). As a result of this new fashion, the King Charles Spaniel of the type seen in the early paintings became almost extinct.

It was at this stage that an American, Roswell Eldridge, began to search in England for foundation stock for Toy Spaniels that resembled those in the old paintings, including Sir Edwin Landseer’s “The Cavalier’s Pets.” All he could find were the short-faced Charlies. Eldridge persisted, persuading the Kennel Club in 1926 to allow him to offer prizes for five years at Crufts Dog Show – twenty-five pounds sterling for the best dog and twenty-five pounds sterling for the best dog and best bitch of the Blenheim variety as seen in King Charles II’s reign. The following is a quotation taken from Crufts’ catalog: “As shown in the pictures of King Charles II’s time, long face no stop, flat skull, not inclined to be domed and with the spot in the center of the skull” and the prizes to go to the nearest to the type described.

No one among the King Charles breeders took this challenge very seriously as they had worked hard for years to do away with the long nose. Gradually, as the big prizes came to an end, only people really interested in reviving the dogs as they once had been were left to carry on the breeding experiment. At the end of five years little had been achieved, and the Kennel Club was of the opinion that the dogs were not in sufficient numbers, nor of a single type, to merit a breed registration separate from the Charlies.

In 1928 a dog owned by Miss Mostyn Walker, Ann’s Son, was awarded the prize. (Unfortunately Roswell Eldridge died in 1928 at age 70, only a month before Crufts, so he never saw the results of his challenge prizes.) It was in the same year that a breed club was founded, and the name Cavalier King Charles Spaniel was chosen. It was very important that the association with the name King Charles Spaniel be kept as most breeders bred back to the original type by way of the long-faced throwouts from the kennels of the short-faced variety breeders. Some of the stock threw back to the long-faced variety very quickly. Pioneers were often accused of using outcrosses to other suitable breeds to get the long faces, but this was not true, and crossing to other breeds was not recommended by the club.

At the first meeting of the club, held the second day of Crufts in 1928, the standard of the breed was drawn up; it was practically the same as it is today. Ann’s Son was placed on the table as the live example, and club members brought all the reproductions of pictures of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries they could muster. As this was a new and tremendous opportunity to achieve a really worthwhile breed, it was agreed that as far as possible, the Cavalier should be guarded from fashion, and there was to be no trimming. A perfectly natural dog was desired and was not to be spoiled to suit individual tastes, or as the saying goes, “carved into shape.” Kennel Club recognition was still withheld, and progress was slow, but gradually people became aware that the movement toward the “old type” King Charles Spaniel had come to stay. In 1945 the Kennel Club granted separate registration and awarded Challenge Certificates to allow the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel to gain their championships.

The effort by Roswell Eldridge to bring back the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel eventually surpassed its short nosed cousin in popularity, achieving American Kennel Club recognition in 1996.